Fight, Flight, or Live in Harmony? Managed Retreat from Disappearing Shores

Why managed retreat?

Surfer’s Point in Ventura, California was one of the world’s top surfing destinations, renowned for its waves. But over time, these waves eroded the shoreline, causing structural damage to public facilities like parking lots and bike paths. The city had attempted to “harden” the coast, a process of installing concrete or rock structures like breakwaters and seawalls, with little success. It became clear that there was one solution to Surfer Point’s deterioration: managed retreat, otherwise known as coastal realignment.

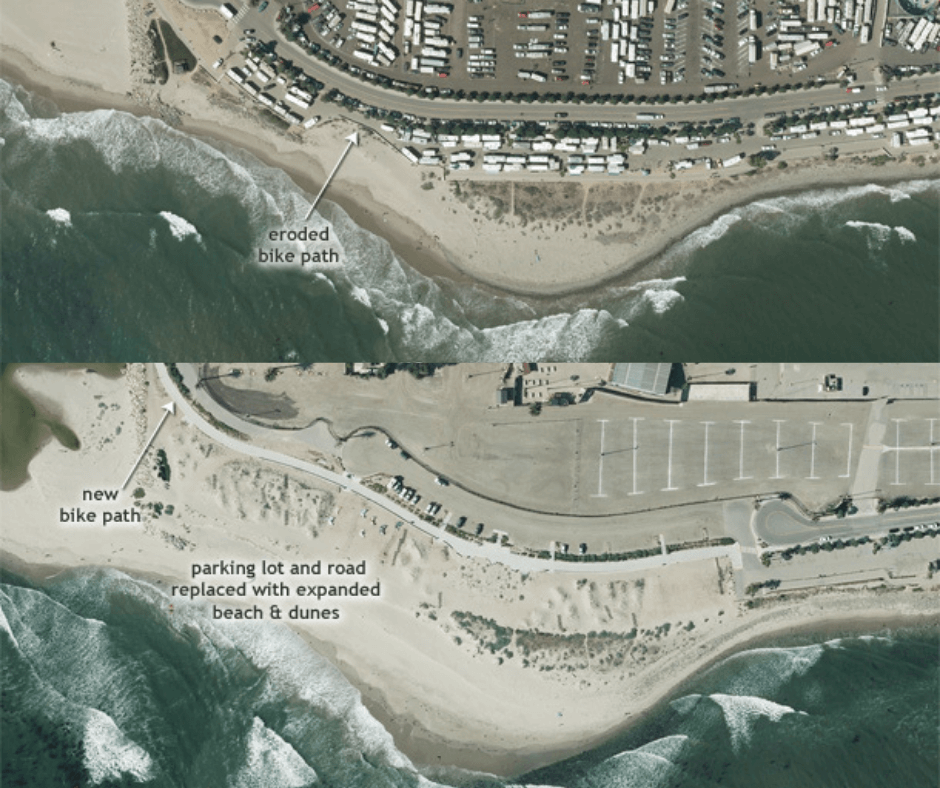

Top: Before the retreat, 2010. Bottom: After the retreat, 2013. The Surfers’ Point Managed Retreat Shoreline Project included shifting parking areas and bike paths over 40 feet away from the coastline. Images taken from Climate.gov

Managed retreat is the process of moving development further inland, and allowing the ocean to re-engineer the coast. It’s a critical climate change adaptation tool that enables coastal communities to continue enjoying the shoreline, and the shoreline to continue existing in its natural state. When sea level accommodation policies like elevating homes, or erosion protection measures like coastal hardening are not effective in stopping damage to infrastructure, managed retreat can protect both community access to the shore and public facilities. By retreating human development from the shoreline, we also protect the natural processes and habitats of the coastal environment.

Top: Eroded beach and waterfront infrastructure at Surfers’ Point, Ventura, CA, 1995. Bottom: Surfers’ Point after Phase 1 restoration, 2015. Images taken from State of Hawaii Office of Planning.

At Ventura’s Surfer’s Point, the ongoing 20-year managed retreat process has successfully removed and relocated public infrastructure and preserved the beach’s surf break. This feat of engineering was a remarkable collaboration of community organizing, stakeholder engagement, and problem-solving.

To retreat or not to retreat?

Managed retreat, however, is a “Wicked Issue”, the term policymakers use to describe a particular kind of conundrum that inherently has no right or wrong answer, and as part of its extreme complexity, has incomplete and socially conflicting resolutions.

In Hawaii, the “wickedness” is acutely felt. As sea levels are rising, many of Hawaii’s waterfront communities are facing extreme erosion, and competing interests are making it difficult to establish a concrete policy. Different stakeholders have political and ideological differences, and budget limitations all make managed retreat a contentious problem.

Moving infrastructure from harm’s way is an opportunity to restore habitats

In New York, Hurricane Sandy prompted the managed retreat of an entire Staten Island community, resulting in environmental benefits.

Oakwood Beach residents formed a committee and initiated a buyout program in collaboration with the state. The program purchased the residents’ homes at pre-hurricane market value and converted the land to natural buffers like breakwater reefs, or recreational spaces like hiking trails. Despite losing the previous neighborhoods, in some cases, locals feel that by restoring natural wetlands they are regaining access to their beaches, and the natural spaces they remember from their childhoods.

If there’s no beach, there’s no beach access. Habitat and infrastructure at risk from eroding Maui resort and condo shores. Image taken from State of Hawaii Office of Planning.

More accessible shorelines could improve locals’ ability to enjoy coastal recreation, and cultural and subsistence activities. If moving development back from the water’s edge leads to restoration of natural shallow water and tidal ecosystems, managed retreat could not only reconnect the community to revived ecosystems, but also bring back natural buffers to protect inland development from sea level rise and increased storminess.

What can be done when we can’t retreat?

Where coastlines can be made more natural, Living Shorelines – the restoration of natural features like dunes and marshlands, can be an effective way to cope with rising seas and erosion. Shifting lifeless concrete coasts to living shores can increase the buffer space for high-water flooding and add ecological value.

Soft edges, or living shorelines, can provide space for ecosystems and storm buffering on urban coasts. Image taken from NOAA.

For coastal areas like ports and certain working waterfronts, despite risk from sea-level rise and erosion, retreating from the water’s edge may not work, and restoring a living shoreline may not be feasible. Where public shoreline access and infrastructure are at risk, and managed retreat isn’t the right option, eco-engineering can provide a win-win solution.

We can achieve both structural stability and ecological regeneration with Natural and Nature-Based Features (NNBF), defined as “landscape features that are used to provide engineering functions relevant to flood risk management while producing additional economic, environmental, and/or social benefits.” Hardened coastal protections (like breakwaters, seawalls, and edge protections) can be engineered to revive natural systems by stimulating oyster reefs, corals, and other ecosystem-engineering organisms that set the foundations for larger species.

ECOncrete® is putting NNBF principles into action. On the edge of the Port of San Diego’s Harbor Island, a new waterfront protection technology is being installed to increase habitat value, and stabilize the Port’s shoreline. A modular single-layer tidepool armor, designed to interlock on each of its eight faces, allows engineered waterfronts to mimic the water retaining features, undercuts, and caves characteristic of natural shallow-water ecosystems.

Ecological coastal armor can protect a shoreline from erosion while providing better conditions for biodiversity.

The biology-enhancing concrete units are designed to increase native flora and fauna, so instead of a barren concrete beach, there’s a platform for a rich community of sessile organisms like oysters, canopy algae, and sea anemones, as well as shelter and nursing ground opportunities for native fish.

Coastal armor designed to mimic natural coastal features, like tidepools, caves, and undercuts.

When erosion and sea-level rise threaten coastal development, we have three options: we can fight the waves with nature-destroying standard technologies, we can flee the coast and allow nature to re-engineer our shores, or we can live in harmony and allow nature to thrive even when hardened coastal protections are necessary.

Without displacing communities, environmentally friendly engineering can increase locals’ access to marine life and living shorelines. The blue designs can inspire community stewardship of the waterfront, and encourage citizen scientists through monitoring and educational activities.

As our communities adapt to the impacts of a changing climate, we must make decisions about how we alter our environment. Let’s choose to design our shores for the benefit of people and the planet.